With no AL or NL West teams in this World Series, we at Midnight Baseball will turn our focus to Red Sox and Cardinals players who used to play out west. Out of all of them, Koji Uehara probably has the highest profile right now. So, with apologies to Carlos, we start with Koji.

Few could have seen such dominance coming this season from Koji Uehara. The Red Sox signed him for one year and $4.25 million, or less than the market value for one win. We can therefore imagine that his suitors were few and miserly. He entered the season behind Joel Hanrahan and Andrew Bailey for the closer’s gig, which doesn’t always go to the best pitcher but shows what the Red Sox thought of him. Bullpens are like totem poles, or pyramids of cheerleaders. They are constructed with a hierarchy, and the people doing the constructing may not have the best criteria behind that hierarchy. The prettiest cheerleader might not be the swellest, the one who deserves the top spot on the pyramid. Coming into the season, Uehara was like a girl who, after many tryouts, finally gets accepted into a cheer squad, but only on the condition that she buy her own uniform, or something. And it’s totally not fair because she has this one awesome, game-changing cheer move, and the baffling thing is, they’ve all seen it before.

The splitter. A rare bird nowadays. Pitchers can send the ball left, right and down, or any combination thereof, but sometimes it seems like one of those directions is prominent for a few years at a time. They fade in and out of favor every few years. A few years ago the cutter was a-buzzing. Sports Illustrated even did a story about it title, “This Is The Game Changer.” There’s been backlash since, notably from the Orioles organization, which has stated that they don’t want their pitching prospects throwing cutters because they think it weakens the arm and saps velocity out of the regular fastball. They may be right, or they just be fucking with the rest of the league. Is Dan Duquette laughing in his office with his underlings, saying “I can’t believe they bought it!”? Is Dan Duquette even the GM of the Orioles still? Is this paragraph going anywhere?

Anyway, on the back of the splitter, Uehara has tossed a historic season for baserunner prevention, as Jonah Keri already described. Perhaps relievers around the league, borderline major leaguers and replacement-level types, will copy the pitch hoping to apea small part of his success. A split-finger renaissance! That’d be cool, but that’s not something we can measure just yet. We can measure how valuable the splitter’s been: the most valuable pitch of its kind in the league, and with the most value per one hundred pitches thrown among pitchers with minimum 50 innings pitched.

Right about now you are probably thinking that Uehara’s great year is the result of some lucky fluctuation–BABIP maybe, or park factors. Uehara’s always had the splitter, ever since he was a suckling babe, and in seasons past he merely very good. What gives?, say you, because you get angry when curious. Well, give me a second, damn it. I can explain.

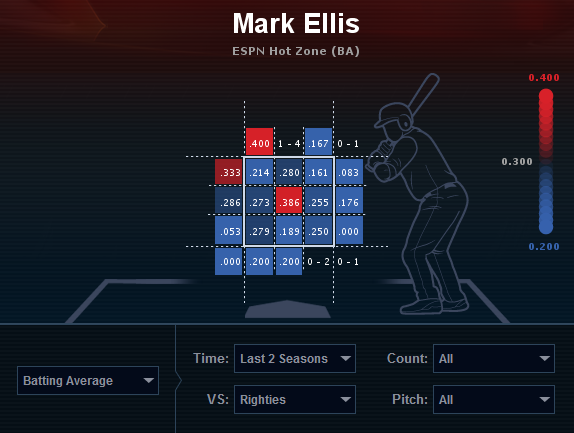

Uehara’s splitter is good enough that he doesn’t need to instill uncertainty in the hitter to be successful with it. (Look at this page again. Of all breaking pitches, Uehara’s splitter is like eighth-most valuable in the league, even though he’s pitched fewer than 80 innings.) Every pitcher has one or two pitches that just plain aren’t as good as his feature stuff. The reason they keep those pitches around is to give the hitter more things to think about. The more pieces you have in chess, the more moves you can make. Except Uehara is finding out that his splitter works just fine even if the hitter doesn’t have to worry about his cutter and even if he throws it more than the fastball. By cutting out the worst parts of his game, Uehara improved.

Don’t worry about the curveball. He’s threw three of them this season, so you can’t even see it on the graph. One of those three went in for a strike. Here it is.

That leaves two main takeaways: 1) Uehara has dropped the cutter this postseason and 2) he’s been increasing usage of his splitter ever since 2011. It has always been his put-away pitch, thrown more in two-strike counts. This postseason, and to a lesser extent this season, he has thrown the splitter as much as he used to when he wanted to strike motherfuckers out. And now, when he has two strikes, the odds of him throwing a splitter are less like a coin flip and more like the odds of getting a prime number when rolling a die. (EMBRACE THE NERD INSIDE.)

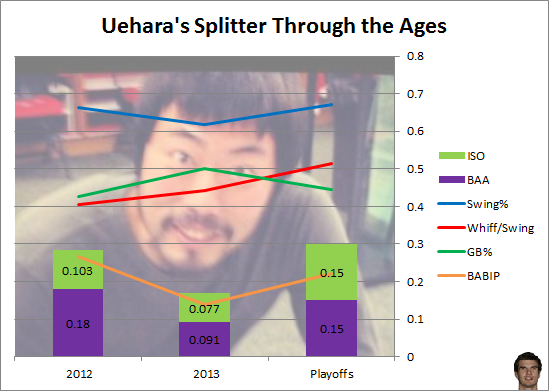

You would think the splitter’s value would dilute with all the extra volume but it doesn’t The graph below suggests that in some aspects it is actually getting better results.

Hitters swung at the splitter a little less but when they did they whiffed more, or if they made contact it was more likely to be into the ground, this season compared to last. So far this postseason, hitters are flailing more than ever. Despite these gains, the bottom half of the graph suggests that Uehara’s improvement is tied strongly to BABIP. The colored bars add up to slugging percentage, and their height matches up well with the BABIP line, suggesting that cursed fluctuations are at least partly guilty for that abominable .168 slugging hitters put up against the splitter this season. Even with a normal-ish BABIP of .267 (as it was in 2012), Uehara’s splitter still held hitters to .283 in slugging. And if you take out Jose Lobaton’s definition-of-an-aberration homer, Uehara’s slugging allowed this postseason would be substantially less than the still-very-low .300. There’s really no way to make these numbers look bad.

You can take a look at FanGraphs leaderboards and find that Uehara’s splitter doesn’t have exceptional movement. Neither it nor his fastball have overpowering velocity. Deception, guile and location serve to make his splitter exceptional. Here’s a zone map of his spliiter from the ALCS.

Low low low! Lower than the prices at Costco. (My mom works there. Love you, mom.) Dude hits his spots. That’s either command or control. I can’t remember how the nerds are classifying them these days. Just look at these putaway pitches from 2012–since this is a west-themed blog, I looked at his time with the Rangers. I found the games in which he was called to enter into the most crucial situations. Then I found the most crucial at-bats in those appearances. In a fit of noteworthy luck, those at-bats came against Michael Saunders, Evan Longoria, Mike Trout, and Edwin Encarnacion, three of whom are some of the best hitters in the league and one of whom is left-handed. So we get to see Uehara face hitters of both handednesses. All of these are two-strike pitches, all of the two-strike pitches thrown against these hitters.

Aside from Edwin’s all-fastball at-bat, Uehara stuck with the splitter. I think the fastball to Trout was meant to back him off some, but I don’t know if Uehara is one of those guys. I haven’t heard that about him, but then again you never hear announcers call an Asian player a bulldog or a firebrand. Announcers are usually middle-aged white guys and they love Texans and big country gentlemen. They don’t like city boys, such as Zitocakes with his yoga, and they respect Asians from a distance, as with Ichiro. There are plenty of cultural barriers between foreign pitchers and the national media: language, customs, training regimens, expectations of privacy, facial hair. We know, at the very least, that Uehara has busted the last one down.